|

...continued from the previous page

WATER

Water is one of the important ingredients for making sake. Rigid restrictions are observed for the concentrations of certain chemical substances that can affect the taste and quality of sake. The water used is almost always groundwater or well water. Urban breweries usually import water from other areas, because of the difficulty of getting water of sufficient quality locally.

BREWING

MOROMI, THE MAIN MASH

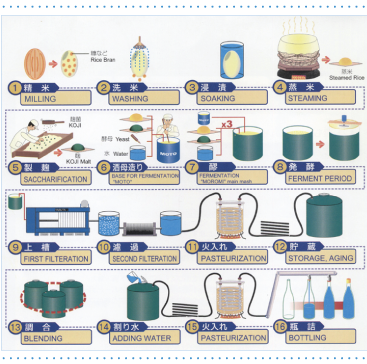

Sake is produced by the multiple parallel fermentation of rice. The rice is first polished to remove the protein and oils from the exterior of the rice grains, leaving behind starch. Thorough milling leads to fewer congeners and generally a more desirable product.

Newly polished rice is allowed to "rest" until it has absorbed enough moisture from the air so that it will not crack when immersed in water. After this resting period, the rice is washed clean of the rice powder produced during milling and then steeped in water. The length of time depends on the degree to which the rice was polished, ranging from several hours or even overnight for an ordinary milling to just minutes for highly polished rice.

After soaking, the rice is steamed on a conveyor belt. The degree of cooking must be carefully controlled; overcooked rice will ferment too quickly for flavors to develop well and undercooked rice will only ferment on the outside. The steamed rice is then cooled and divided into portions for different uses.

The microorganism Aspergillus oryzae is sprinkled onto the steamed rice and allowed to ferment for 5-7days (Uno et al., 2009). After this initial fermentation period, water and the yeast culture Saccharomyces cerevisiae are added to the koji (rice and mold mixture) and allowed to incubate at four degrees Celsius for about seven days (Uno et al., 2009). Over the next four days, pre-incubated mixture of steamed rice (90 kg), fermentated rice (90 kg) and water (440L) are added to the fermented mixture in three series (Uno et al., 2009).

This staggered approach allows time for the yeast to keep up with the increased volume. The mixture is now known as the main mash, or moromi.

The main mash then ferments, at approximately 15-20 degrees Celsius for 2–3 weeks. With high-grade sake, fermentation is deliberately slowed by lowering the temperature to 10°C (50°F) or less. Unlike malt for beer, rice for sake does not contain the amylase necessary for converting starch to sugar and so it must undergo a process of multiple fermentation. The addition of A. oryzae provides the necessary amylases, glucoamylases, and proteases to hydrolyze the nutrients of the rice to support the growth of the yeast (S.cerevisiae) (Uno et al., 2009). In sake production, these two processes take place at the same time rather than in separate steps, so sake is said to be made by multiple parallel fermentation. The main mash then ferments, at approximately 15-20 degrees Celsius for 2–3 weeks. With high-grade sake, fermentation is deliberately slowed by lowering the temperature to 10°C (50°F) or less. Unlike malt for beer, rice for sake does not contain the amylase necessary for converting starch to sugar and so it must undergo a process of multiple fermentation. The addition of A. oryzae provides the necessary amylases, glucoamylases, and proteases to hydrolyze the nutrients of the rice to support the growth of the yeast (S.cerevisiae) (Uno et al., 2009). In sake production, these two processes take place at the same time rather than in separate steps, so sake is said to be made by multiple parallel fermentation.

After fermentation, sake is extracted from the solid mixtures through a filtration process. For some types of sake, a small amount of distilled alcohol, called brewer's alcohol, is added before pressing in order to extract flavors and aromas that would otherwise remain behind in the solids.In cheap sake, a large amount of brewer’s alcohol might be added to increase the volume of sake produced. Next, the remaining lees (a fine sediment) are removed, and the sake is carbon filtered and pasteurized. T he sake is allowed to rest and mature and then usually diluted with water to lower the alcohol content from around 20% to 15% or so, before finally being bottled. he sake is allowed to rest and mature and then usually diluted with water to lower the alcohol content from around 20% to 15% or so, before finally being bottled.

MATURING

The process during which the sake grows into a qualityproduct during storage is called maturing.

Mature sake has reached its ideal point of growth.New sake is not liked because of its rough taste, whereas mature sake is mild, smooth and rich. However, if it is too mature, it also develops a rough taste. Nine to twelve months are required for sake to mature.

Aging is caused by physical and chemical factors such as oxygen supply, the broad application of external heat, nitrogen oxides, aldehydes and amino acids, among other unknown factors. It is said that Saussureae radix from the Japan cedar material of a barrel containing maturing sake comes to be valued, so the barrel is considered indispensable.

TŌJI

Tōji is the job title of the sake brewer. It is a highly respected job in the Japanese society, with tōji being regarded like musicians or painters. The title of tōji was historically passed on from father to son; today new  tōji are either veteran brewery workers or are trained at universities. While modern breweries with refrigeration and cooling tanks operate year-round, most old-fashioned sake breweries are seasonal,operating only in the cool winter months. During the summer and fall most tōji work elsewhere, and are commonly found on farms, only periodically returning to the brewery to supervise storage conditions or bottling operations. tōji are either veteran brewery workers or are trained at universities. While modern breweries with refrigeration and cooling tanks operate year-round, most old-fashioned sake breweries are seasonal,operating only in the cool winter months. During the summer and fall most tōji work elsewhere, and are commonly found on farms, only periodically returning to the brewery to supervise storage conditions or bottling operations.

In Japan sake is served chilled, at room temperature, or heated, depending on the preference of the drinker, the quality of the sake, and the season. Typically, hot sake is a winter drink, and high-grade sake is not drunk hot, because the flavors and aromas will be lost. This masking of flavor is the reason that low-quality and old sake is often served hot.

Sake is usually drunk from small cups called choko, and poured into the choko from ceramic flasks called tokkuri. Saucer-like cups called sakazuki are also used, most commonly at weddings and other ceremonial occasions. Recently, footed glasses made specifically for premium sake have also come into use.

Another traditional cup is the masu, a box usually made of hinoki or sugi, which was originally used for measuring rice. In some Japanese restaurants, as a show of generosity, the server may put a glass inside the masu or put the masu on a saucer and pour until sake overflows and fills both containers.

Aside from being served straight, sake can be used as a mixer for cocktails, such as tamagozake, saketinis, nogasake, or the sake bomb.

|